So, about an hour of extra free time today, I get to write. 🙂

If you’ve found your way to my blog using Google, odds are you already know a bit about what mycorrhiza are. You may have seen a wiki page or maybe even a commercial product. Because I am more than a little fascinated by the subject, I will try to provide you with some information about it that might otherwise be a little hard to glean from the Internet.

Mycorrhiza are symbiotic relationships between plants and fungi, which was largely unknown to us until it’s relatively recent discovery. As it turns out, most land plants take part in them and the development of mycorrhiza probably played a key role in getting plants to first colonise dry land millions of years ago.

Fungi are from the human perspective a very unique type of living organism. While to us they are familiar as their multicellular fruiting bodies, aka Mushrooms, but the main body of the fungus is usually the below-ground part which is composed of a mesh of mycelium. To us this may simply be the rather unremarkable “roots” of the fungus, but fungi are very different from both plants and animals… Fungi feed by growing through their food and digesting it on the outside of their bodies, then absorbing the nutrients. Each strand of mycellium is only a single cell thick, so the mesh is very fine, and the cellular contents within this mycellium can flow very quickly from where it is available to where it is needed.

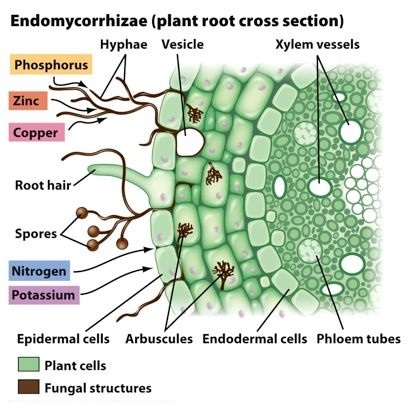

This makes fungi a lot better at certain tasks than both plants and animals. Notably in the case of plants, they are able to extract minerals and water out of soils that are otherwise either toxic or unavailable to the plant. The relationship between plant roots and fungi is very old and both plants and mycorrhizal fungi have specialised organs that serve to interface between the two species. The plant uses these organs to get nutrients and water from the fungus, and the fungus feeds of of hexoses, a special type of sugar produced by the plants specifically for the fungus.

This makes fungi a lot better at certain tasks than both plants and animals. Notably in the case of plants, they are able to extract minerals and water out of soils that are otherwise either toxic or unavailable to the plant. The relationship between plant roots and fungi is very old and both plants and mycorrhizal fungi have specialised organs that serve to interface between the two species. The plant uses these organs to get nutrients and water from the fungus, and the fungus feeds of of hexoses, a special type of sugar produced by the plants specifically for the fungus.

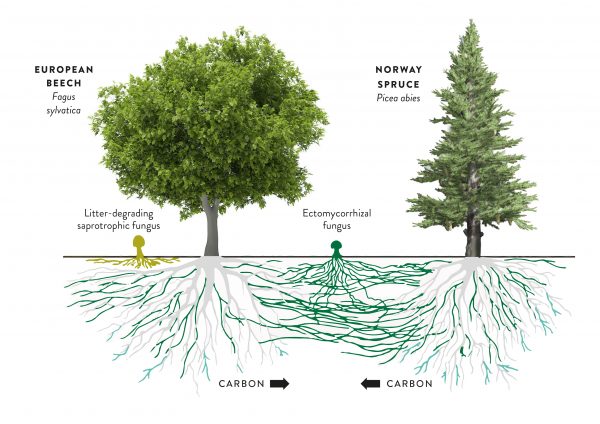

What is so interesting about mycorrhizal fungi however is that the mesh of mycellium, is not a branching tree-like structure like with plant roots, it is a web. The same mycorrhizal fungi can be linked with multiple different plants and the fungal mesh is perfectly capable of transporting chemicals between different plants. There has been research done that shows that tomato plants can share chemical signals through this network. There is other research done that shows that plants of different species can feed one-another through the network.

This somewhat challenges the long-standing belief that plants compete for resources in their natural environment, where only the most efficient survive. If most land plants take part of a local mycorrhizal network then in fact, the forest or the grassland is socialism. Or at least that’s what the people selling you your mycorrhizal fungus spores are trying to convince you of. That your plant will be automatically better off if well interfaced with a local network.

I’ve spoken to several scientists who are actively researching the subject and in every case they are rather frustrated with the assumptions made by the companies rushing to capitalise on the discovery of mycorrhiza. The truth is: It’s complicated. After the excitement of the initial discoveries wore off, scientists quickly found that there are as many different mycorrhizal fungi as there are plants and that all behave in different ways and many of them compete in the natural environment for their precious resource — plants. Different plants will invest different amounts of resources in the network and some fungi are selective about which plants they interface with. Bottom line, it will all require decades more of research before we can say anything for sure.

What I like to think (which is to say there is some foundation of this in the current research into mycorrhiza, but I am not a scientist) is that in nature, there are all of these different systems and what nature ends up using is whatever works best in a particular scenario. If different fungi are competing for plants and therefore only the most successful survive, some of the time this means that perfectly socialist networks will be prevalent. And since we have observed examples of this being the case, I would say it’s safe to say this kind of system can work. The plants and the fungi are able to determine this on their own without human interference, even in a system where abuse is quite possible and is probably even advantageous in some cases. That is, there are both plants and fungi that take advantage of the network, because they can. But it seems in the grand scheme of things, networks that do not have such individuals work better and out-compete networks that do contain exploitation.

What I like to think (which is to say there is some foundation of this in the current research into mycorrhiza, but I am not a scientist) is that in nature, there are all of these different systems and what nature ends up using is whatever works best in a particular scenario. If different fungi are competing for plants and therefore only the most successful survive, some of the time this means that perfectly socialist networks will be prevalent. And since we have observed examples of this being the case, I would say it’s safe to say this kind of system can work. The plants and the fungi are able to determine this on their own without human interference, even in a system where abuse is quite possible and is probably even advantageous in some cases. That is, there are both plants and fungi that take advantage of the network, because they can. But it seems in the grand scheme of things, networks that do not have such individuals work better and out-compete networks that do contain exploitation.

What I consider to be the truly mind-blown moment however, is that if you look at the most typical average back-yard you can see examples of all of this everywhere. Both the woodland and grassland ecosystems in fact harbour mycorrhizal networks in their soils. For trees, research shows that trees up to 14 meters away from each-other are linked, whereas in fields of grass the network probably spans the entire thing. If you have a small tree planted near a large tree, even if they are not the same species, odds are the larger tree is feeding the younger one.

LP,

Jure

I read this article completely about the difference of newest and previous technologies, it’s awesome article.